| Culture |

Stereotype and Tradition in Upper Michigan

|

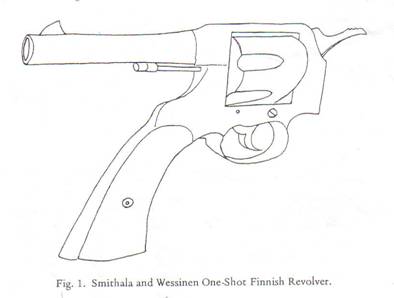

| Visual ethnic slur. Smith and Wesson is fennicized using common surname endings. Reprinted with permission from the Journal of American Folklore, volume 89, number 351. |

The role that stereotype plays in the regional culture of Upper Michigan residents and of the ethnic Finns is strong and has been since early settlers came to the area. Today, a seemingly dualistic relationship between Michigan’s two peninsulas has developed, and negative stereotypes about the other abound on both sides. While much of Lower Michigan stereotypical images focus on the urban world of Detroit, Upper Michigan stereotypes are centered on rurality and the continued assertion of ethnic life that many residents have. Upper Michigan residents are teased about their accents, which the Finnish language strongly influences. They are portrayed as alcoholic and sometimes slow-witted. Numerous negative images exist, making contact between the two sides difficult at times. There is an imbalanced assumption among some that life is easier and better, more cultured, downstate.

|

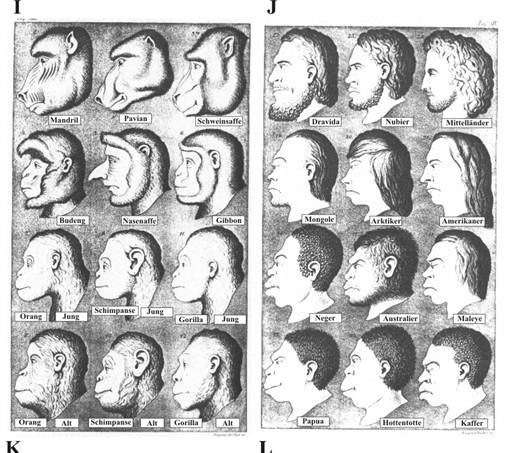

| “Social scientific” graphics by German anthropologist Ernst Haeckel illustrating assumed inherent traits common among ethnic groups. This particular example also suggests a continuity between apes and humans, which was used as an offensive twist to Darwin’s theory of evolution. These biased studies were used to prove that there were inalienable differences between groups of people, and that, essentially, Caucasian Anglo-Saxons (Mittelanders in this rendering) were at the apex of human- and primate- evolution. Finns and Sami were alleged to belong to the “Mongole” classification. |

For Finns, stereotypes are heightened. Before coming to the United States, Finns were classified by early anthropologists such as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach as being of the Mongolian, or Asiatic race. This assumption came from the fact that Finns and their linguistically and culturally related neighbors, the Sami and Estonians, had uncertain origins, but that all signs pointed east, to the Ural Mountains or possibly much farther. This “information,” used by some as positive propaganda for the uniqueness of Finnish culture and as proof of their need for separate statehood from the Russian Empire, was also used as proof of Finnish inferiority and as justification for discrimination. In the Copper Country, these racial theories were also known. Armas K.E. Holmio, in his book, A History of the Finns in Michigan, relates the story of Helmi Warren, who, as a school child in the 1890s was turned away from a playmate’s doorstep when “the friend’s mother realized that her daughter’s playmate was a Finn. Helmi was turned away immediately, and the daughter of the house was forbidden to associate with ‘that Mongolian’” (2001:17).

|

| Competitors in the Heikinpäivä Polar Bear Dive, 2004. One participant carries a makeshift Finnish flag with a sign that reads, “Crazy Finns.” This phrase is frequently used to explain away “Finnish” behavior considered odd by others, such as their use of the sauna bath, which would often be followed by a dive into a snowbank or a frozen body of water. Photograph courtesy City of Hancock Finnish Theme Committee/ Mary Pekkala. |

Finnish culture was regarded to be as exotic as their assumed racial origins, with their use of the sauna bath seen as unseemly, immoral, and possibly supernatural behavior. Contributing also to imbalanced imagery of Finns was their tradition of the noita. As folklorist Richard Dorson described in his 1952 book on Upper Michigan folklore, Bloodstoppers and Bearwalkers,

“The noita, variously described as a religious magician, a wizard, or a healer,played a prominent role in village life. He cured the sick, with or without herbs,charmed and cursed evildoers, and on special occasions used his powers to defend his people from the enemy and so became a national folk hero.”

The noita is one of the last glimmers of Finnish shamanism, and as such, is a powerful symbol of Finnish indigenous culture. In a 2004 interview, Dave Riutta stated that Heikki Lunta was inspired in part by the stereotype of the Native American “rain dance,” but he, and numerous others in the ethnic community have also acknowledged these obvious ties to Finnish cultural imagery. Robert Glantz, in an article for the Finnish-American Reporter, directly addresses this connection: “Unconsciously perhaps, composer Riutta tapped into the archaic pulse of pagan Finland, the shamanistic rhythm of the Kalevala, to empower his Heikki Lunta with a blue-eyed mojo, capable of moving the heavens to snow.”

Adding to this picture was the fact that Finnish language does not belong to the Indo-European language family, making their language just as strange and exotic as their customs, and so Finns were further marginalized from other immigrant groups. Creating communities in which their language and traditions could continue to exist, Finns have maintained a strong sense of identity through to the present generation of youth. While certain elements of the immigrant culture have ceased to exist, or have radically changed, Finnish-American ties to their heritage culture have resulted in a strong sense of tradition as evidenced in foodways, vernacular architecture, religion, and language.

|

| Distribution of Finno-Ugric languages in Europe and Western Asia reveals a strong northeastern orientation with regards to Europe. Finno-Ugric languages are unique in that they are not a part of the Indo-European language family, languages of which are spoken by approximately 97% of Europeans. Image used under fair use laws from wikipedia.org. |

Since the end of mass immigration, Upper Michigan residents of all ethnicities have created a unique culture, involving such things as regional foodways, a dialect, and humor, among other factors. With newcomers to the area, including tourists, seasonal residents, retirees, and permanent residents from afar, identity issues have become blurred. These newcomers do not recognize the difference between Finns, Italians, the Cornish, and the numerous other ethnic groups in the region and so all of the native residents are lumped into the category of a “Yooper.”

This is true, too, of those from downstate who do not visit the area, but use their limited knowledge of Upper Michigan to judge the residents as rural, backwards, and uneducated. Their interpretation of the area as a monoculture devoid of diversity is as far from the truth as possible. This judgment is widespread, however, and creates a sense of imbalance between natives to the Upper Peninsula and any others who may visit the region.

As with many cultures, stereotype and identity politics are bound together. Finnish Americans, as the majority subset of the Upper Michigan population base, are key to the formation of such stereotypes, and are also key to determining what they want for outsiders to really see.